“Proclamation Day” on January 1, 1916, appears to be the first commemoration of freedom from enslavement by black residents of St. Pete. Two events marked the occasion. They give us a poignant glimpse of interracial relationship patterns that still play out in the present. They also show us the amazing strength of a black community laboring under oppression on every hand.

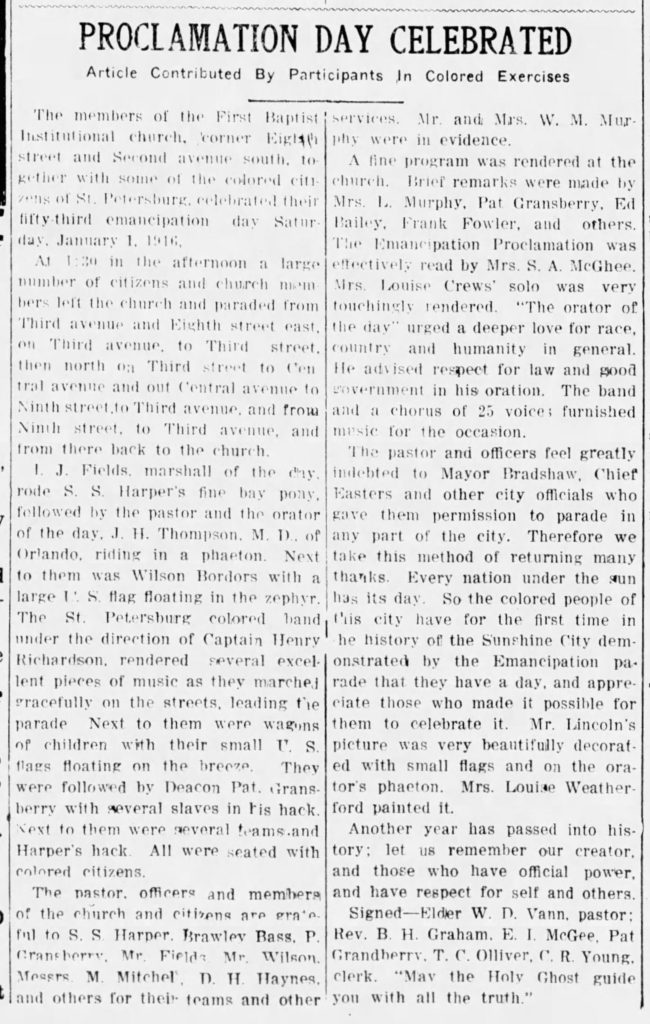

Parade & Program by First Baptist Institutional

One event was hosted by First Baptist Institutional Church, the second-oldest black congregation in St. Petersburg, still in existence today.

It included an 18-block parade that spirited former slaves in a horse-drawn hack and children in wagons waving U.S. flags. The “St. Petersburg colored band” performed.

This was followed by a program of solo and choir music, a speech by Dr. J.H. Thompson, urging a “deeper love for race, the county, and humanity,” and a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Event organizers were grateful to City officials for allowing a freedom celebration “for the first time in the history of the Sunshine City,” all the more because it took place partly outside of the boundaries of black life.

The parade was permitted to skirt downtown and travel six blocks on Central Avenue, north of the Gas Plant and Peppertown neighborhoods (from 3rd and 9th Streets).

Afterwards, the organizers wrote, “The pastor and officers feel greatly indebted to Mayor Bradshaw, Chief Easters and other city officials who gave them permission to parade in any part of the city.”

The exchange reveals a recurring pattern in race relations in St. Pete and elsewhere: white leaders offering African Americans symbolic gestures and small-scale advances while denying them participation in power and opportunity.

The officials who allowed the ceremony were at the forefront of blatantly racist City policies that kept black residents at the bottom of the economic hierarchy.

Bradshaw was one of the leading citizens who stoked support for “whites only” primary elections in St. Petersburg. During his 1913 campaign, Bradshaw declared that he “wanted to go into public office as the choice of the white voters…and would rather not have the office than to rely on the negroes to win.”

He and Police Chief A.J. Easters helped to enshrine a City-run convict labor program that targeted African Americans for arrest to serve as a labor pool.

During his time as chief (1906 to 1921), Easters presided over the arrest and forced labor of countless African Americans from the Gas Plant area.

The two men also took part in a successful campaign to squash the black vote in the contentious election of 1916.

On the other hand, the festivities showcase the artistry, organizing power and budding wealth of African Americans during the era. Several black businessmen contributed teams of horses and wagons to form the parade; an artist – Louise Weatherford – hand-painted a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln; Captain Henry Richardson directed the band to produce “excellent pieces.”

As one indicator of the financial capacity of the community at the time, of the roughly 470 black households in the city, nearly 150 homes were owner-occupied. The men whose horses powered the parade were among the most well-endowed land and property owners in the city – black or white.

Banquet for Former Slaves at Black School

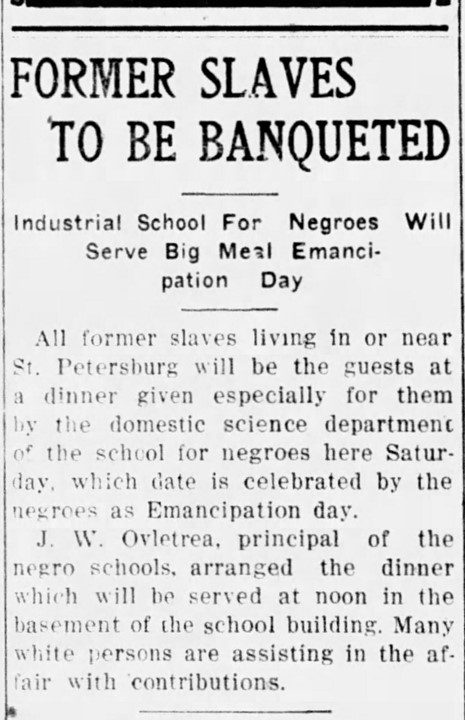

The other event was a banquet for former slaves, held in the basement of a black school in the Gas Plant neighborhood. An announcement of the dinner noted that “Many white persons were assisting in the affair with contributions.” White donors funded the annual slave dinner for at least three years.

At the time, the school was a focal point of black protests over the gap in education available to black versus white students. The policy of the school district limited blacks to “industrial” training to prepare them for menial labor jobs.

Black leaders and parents were pushing for a college-track curriculum for black children.

School principal, John Ovletrea, wrote of the controversy:

“This community is cursed by the presence of a few misdirected, but possibly well meaning negroes who see their salvation through the hazy labrynth (sic) of artificial life, through an educational system aiming at the skies and forgetting the ground on which they live…

“The negro public schools of St. Petersburg are teaching its pupils the dignity of labor…

“These schools are teaching the girls to see the independence and dignity that comes from knowing how to do the domestic arts better than any other woman in the community.

“We are teaching our boys to see that there is as much dignity in tilling a farm as in preaching a sermon.”

Oveltrea (a black man) typified the “house negro” archetype (an African American whose proximity to whites in power earns them comparatively better treatment than other African Americans, and thus inclines them to the ideology of whites in power).

This is an inevitably incomplete and possibly unfair picture of Oveltrea. He was no doubt an accomplished man. Yet his posture (open disdain for fellow black leaders) reveals a repeated pattern in black-white relations in St. Petersburg and elsewhere:

Whites in power supporting (and siding with, when needed) African Americans most willing to accommodate rather than challenge discrimination; and in this latter group, blacks often choosing to undermine or discount black voices that dissent from the status quo, in order to maintain peripheral access to opportunity.

In response to the protest, white philanthropists doubled down on giving to the school. The Times published a glowing report on Ovletrea and his work (which is believed to be the first feature article of positive bent, ever done on the work of an African American by the newspaper).

The debate also shines a light on the rich tradition of advocacy by African Americans in St. Petersburg.

Some believe that our fight for equal rights began during the Civil Rights Era. But advocacy for better education for black children has enjoyed the uninterrupted support of St. Petersburg’s black community since before the turn of the 20th century.

SOURCES:

Library Press@UF, Arsenault, Ray, “St. Petersburg and the Florida Dream, 1888-1950,” Reissued 2017

St. Petersburg Times, “Former Slaves To Be Banqueted; Industrial School For Negroes Will Serve Big Meal Emancipation Day,” December 30, 1915

St. Petersburg Times, “Proclamation Day Celebration; Article Contributed by Participants in Colored Exercises,” January 7, 1916

St. Petersburg Times, Editorial, “Booker T. Washington,” by J.W. Ovletrea, Prin. Negro Public Schools, November 15, 1916

St. Petersburg Police Department, Former Police Chiefs, available here.