In Honor of Black History Month 2023

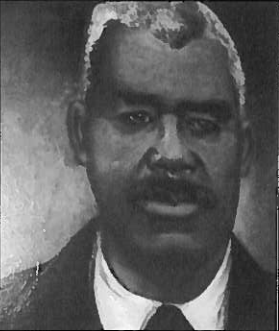

Elder Jordan, Sr. is recognized as one of St. Petersburg’s most famous black business pioneers. To my knowledge, he is the only African American with a statue of his likeness planted in St. Petersburg, and one of only a handful of African Americans memorialized with buildings named in their honor.

Yet we know so little about his business achievements and community contributions.

Like many black legends and leaders of the past, Jordan’s life and times were never captured by local media of the early 20th century. Nor did he appear in the “who’s who” of city business leaders published in 1924 when Jordan was at the height of his influence and impact.

As a result, much of the work of Jordan and his contemporaries was buried in the past until recently. New research has uncovered a trove of insights into the business activities of the famed entrepreneur.

Below is a summary of some preliminary discoveries about a man of incredible accomplishment, especially for the era in which he lived.

Jordan was prolific; he bought, sold, and lost dozens of properties

The part of Jordan’s story most often repeated is that he was born a slave in 1848 and by his death in 1936, had helped spearhead development of the 22nd Street corridor and surrounding residential areas, which – soon after his passing – blossomed into the “main street” of St. Petersburg’s African American community.

New research shows that Jordan also contributed to development in other parts of the city’s segregated black community. He bought, developed and owned properties spanning at least 12 subdivisions.

He also played a founder’s role in the establishment of the Gas Plant community which is where his earliest acquisitions and projects took place.

Based upon my still-partial inventory of Elder Jordan’s real estate transactions, he and three of his sons bought, sold, and lost approximately 93 properties – including parcels of land that range in size from single lots (or portions thereof) to 10 acres.

It should be noted that this is very likely an undercount of the Jordan family’s real estate activities. Antique media archives are difficult to search comprehensively, particularly in the 1920s; and as an important caveat, I have not yet delved into the portfolios of Jordan’s sons.

Of the total properties so far identified, Elder Jordan, Sr. owned at least 63; his son Elder, Jr. turned over 14; his son McKinley owned at least three properties; and 13 properties were ascribed to “Elder Jordan” without indication of Jr. or Sr.

Jordan also developed an undetermined number of his properties. I’ve come across 18 permit-related reports for Jordan and his sons (more on them below). They entail construction of four mixed-used projects (with both housing and commercial space), two multifamily housing developments, seven single family homes and two commercial properties.

A window into how Jordan built his empire

It’s obvious that Jordan pulled himself up by his bootstraps. But property records give us a window into how Jordan went from working as a fruit vendor in 1904, to owning more property than any black man living in St. Petersburg in 1927 (by my count, approximately 55 parcels of land of varying sizes and multiple business enterprises and establishments).

One of Jordan’s secrets to success: he religiously plowed his savings and net income into real estate and business ventures. This is clear from the trajectory of Jordan’s known business dealings.

He also occasionally generated cash by selling properties, and several times partnered with family members and third parties (both white and black) to acquire properties and seed business enterprises.

According to historian Ray Arsenault, Jordan and his wife, Mary Frances Strobles, “brought their family to St. Petersburg in 1904 and opened a produce stand in their home on 9th Street South. Jordan made deliveries using a horse-drawn wagon and opened a livery stable. With the proceeds and the money he brought from his farm, Jordan invested in real estate.”

My research shows that within less than two years of their arrival (if not sooner), Jordan had already purchased two lots of an undetermined size. Then in 1907, he built what appears to have been his first mixed-use property.

The newspaper described it as a structure on 2nd Avenue South and 10th Street where “space is reserved in front for two stores and the rest will be a fourteen-room boarding house.”

Housing rental income may have funded Jordan’s future land acquisitions. He built another five-room house in 1908, and by the mid-1910s had amassed apparently sizable holdings.

In 1914, he sold the City of St. Petersburg the land it needed to build the municipal gas plant that accounts for the moniker given the roughly 42-block neighborhood known as the “Gas Plant.” Interestingly, the purchase was necessitated by white backlash to the site originally chosen for the plant (in the Bayboro area).

We see another large property co-owned by Jordan in the news in 1916 when he and another party suffered a forced foreclosure sale of 10 acres.

The papers show a second forced sale of an apparently large Jordan property in 1919 – a foreclosure by First National Bank of St. Petersburg.

Despite the hits to his portfolio, it doesn’t appear that Jordan had a net loss in the 1910s. During that decade, Jordan suffered as least three forced sales of property and had three traditional sales, but also made at least three acquisitions and secured permits for construction on three properties.

My count (though incomplete) shows that Jordan began the decade with five properties and ended it was 23.

Jordan’s sons were entrepreneurs as well

Historians say that Jordan and his sons built the Manhattan Casino in the 1920s. We see news of the project in September 1923 when the Times reported: “Elder Jordan, Jr., negro, was granted a permit in the building inspector’s office Friday, for the erection of a one story dance pavilion for the negroes. The building is to be located at Twenty-Second street and Seventh avenue south and will cost $4,000. Work will be started next week.”

Jordan, Jr. was also credited with an $8,000 permit in 1926, which the paper noted was “the largest of the day.” The planned structure was a “rooming house” to be located on 12th Avenue South between 24th and 25th Streets.

Jordan, Jr. may have been acting on behalf of his dad in securing the permit; it was Jordan, Sr. who approved a contract for construction of the project to a local contractor named W.N. Thomas. Under the title “Apartments to Begin,” a brief newsclip described the building as two-stories with 10 rooms and ground floor spaces for three retail stores.

Sr. and Jr. also appear to have owned several adjacent properties (though it’s possible that some property labels misnamed or transposed the two men).

Another son – McKinley Jordan – was an entrepreneur. He secured a permit to construct a small apartment building in 1922. An advertisement in 1929 shows McKinley as proprietor of the Jordan Service Station offering, “18 Hour Service, with Courtesy to All.” The business was located at 1351 5th Avenue South.

McKinley went on to join the clergy. By his death in 1944, he was an associate pastor at McCabe Methodist Episcopal Church. Jordan’s youngest son Harry owned a service station on 9th Street.

Jordan’s fate appears to rise with the 1920s boom and fall with the Great Depression

The size and value of Jordan’s portfolio may be unknowable but a notice in the paper in 1937 indicates that he lost wealth during the Great Depression. At the end of the real estate bloom of the 1920s (ca. 1921-26), Jordan was one of the wealthiest black men in the city, if not the wealthiest.

Our visibility is limited but I found two forced sales of properties owned by Jordan during the Great Depression era – in 1930 and again in 1933.

By the time of Jordan’s death in 1936, his estate appears to have dwindled. Under the header “Negro Leaves $3,010 Estate,” a 1937 news clip announced:

“Elder Jordan, Sr., 72, negro, who died in St. Petersburg Nov. 21, 1936, left an estate of $3,000 in real estate and $10 in personal funds, according to the probate papers filed today. He left four sons and five granddaughters.” (Please note, Jordan may have been as old as 88 when he died).

As for the $10 in cash left to his heirs, I have to believe he somehow left more.

Regardless of his net asset balance at end of life, Elder Jordan, Sr.’s legacy is about much more than what he owned and built. For one, he overcame odds that African Americans of today can scarcely imagine and created what was likely the largest black business portfolio in St. Petersburg.

In addition to his work in real estate, Jordan and his sons owned and operated a bus line between Tampa, Clearwater, and St. Petersburg; two gas stations; a produce vending enterprise; and a dancehall and bar. They are also credited with developing a beach for African Americans.

His contributions to community were equally important. According to a plaque on the Jordan statue, he donated the land on which the Jordan park apartments were built (the first public housing development in St. Pete). Arsenault wrote in 2012, that it appears Jordan contributed the land needed to build the Jordan School to accommodate rapid growth of the city’s African American population.

My research finds other unheralded contributions, such as the fundraiser he spearheaded in 1920 for what later became Mercy Hospital. Jordan recruited 22 African American business owners to sponsor the effort.

My hope is that present and future generations will learn from his inspiration.

Click here to see a still-in-process inventory of Jordan Family real estate transactions and records. With ideas, suggestions or questions about this research, please email Latorra Bowles, Project Manager & Research Assistant, Power Broker Media Group at latorra@powerbrokermagazine.com.